We were reminded at the Kelley House this past week that a political campaign without rancor would be a rare thing indeed. The 1934 race for the office of California’s governor provides one example. The Republican candidate was Frank Merriam. The Democratic candidate had been a member of the Socialist Party and was nationally known as the author of “The Jungle” — the horrific 1906 expose of the Chicago meat packing industry — Upton Sinclair. A year before the election Sinclair had published another book entitled, “I, Governor of California and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future,” which laid out his proposed plans to “End Poverty in California.” EPIC became Sinclair’s campaign slogan.

We were reminded at the Kelley House this past week that a political campaign without rancor would be a rare thing indeed. The 1934 race for the office of California’s governor provides one example. The Republican candidate was Frank Merriam. The Democratic candidate had been a member of the Socialist Party and was nationally known as the author of “The Jungle” — the horrific 1906 expose of the Chicago meat packing industry — Upton Sinclair. A year before the election Sinclair had published another book entitled, “I, Governor of California and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future,” which laid out his proposed plans to “End Poverty in California.” EPIC became Sinclair’s campaign slogan.

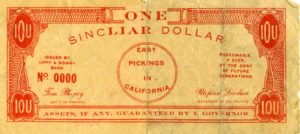

Concrete evidence of one tactic used to smear Sinclair by associating him with the color red (signifying the opposition’s contention that Sinclair’s plans came straight out of Moscow), arrived at the Kelley House Museum in the postal mail by way of a donation of photographs, postcards and other documents belonging to the Mathison family. The item, from the gubernatorial campaign of 1934, was made to resemble a dollar bill and printed with red ink on both sides of a piece of thin paper. Across the top, the words “ONE SINCLIAR DOLLAR” were centered above the words “Easy Pickings in California,” a play on Sinclair’s “End Poverty in California.” To the left of the centered medallion it stated that the paper was “Issued by Uppy & Downy Bank.” To the right was the caveat that this bill was “Redeemable, If Ever, at the Cost of Future Generations”. The bill had two “signatures”: Tom Phoney, Secretary of Finance, and Utopian Sincliar as Governor. The letters “I O U” are substituted for a numeric denomination in each of the bill’s four corners. Along the paper’s bottom, set off in block print, was the caution, “Assets, if any, Guaranteed by I, Governor.” On the reverse side, the insults to Sinclair’s campaign continued with the following summation of statements: “The Red Currency — I, Governor of California, hereby issue this Labor Credit with the Demand that it be accepted as full payment of wages for labor performed and for all merchandise — Not Very Good Anywhere — Good Only in California or Russia — Endure Poverty in California.”

In archival circles, this item is a piece of ephemera, a term used to denote, “the minor transient documents of everyday life.” That definition for paper ephemera came from Maurice Rickards, at one time head of the British Ephemera Society. There is an American equivalent, too.

The particular branch of the Mathison family involved was that of Charles John and Irma Brown Mathison, once residents of Little River, a camp at Ten Mile and, eventually, Fort Bragg. Charles was born in Little River to parents John Peter Mathison and Caroline Mathison, natives of Norway. Irma’s parents were George Tansy and Florence Etta Brown, who raised their children on their farm in Anderson Valley. Charles and Irma Mathison owned a candy shop, The Poppy, on Franklin Street in Fort Bragg and had two children, Robert and Lillian. The “SINCLIAR DOLLAR” was among the things sent to the Kelley House Museum by a distant family member who had inherited the items. Charles would have been about 47 years of age in 1934, Irma 34 years old. It is safe to assume that the Mathisons would have sided with Governor Merriam’s campaign, since Charles had registered as a Republican at one time.

Although Franklin D. Roosevelt did not endorse Sinclair’s campaign, the EPIC movement as conceived by Upton Sinclair has been noted by some historians as a source for concepts that led to programs of the New Deal under the F.D.R. administration.

If you have any “minor transient documents of everyday life” from your Mendocino Coast family, please contact the Kelley House Museum at 707-937-5791 or curator@kelleyhousemuseum.org.

Photo caption: One Side of the “SINCLIAR Dollar”, 1934, Mathison Family File, Kelley House Museum, Inc.