By Katy Tahja

If you didn’t know any better and were not noticing the spelling, you might think “Big River Was Dammed” is about the local watershed’s dark, disturbing history. But this book is about the 27 water-control structures erected by loggers on the river back in the boom days. The dam closest to the mill on the Big River flat was 11 miles upstream; the most distant one was 48 miles away. Why all this dam building?

The first men to log these woods were from New England and Canada where logs were floated to saw mills on the rivers. With no roads or rails, and only oxen to drag the logs, rivers were the path of least resistance. Dams held water back as the river’s water level varied greatly with the seasons. The more water you could put under a log, the farther it would travel downstream. And the loggers wanted those logs to float all the way to the mill.

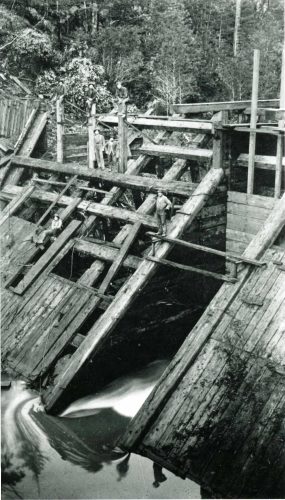

Three types of dams were used. Splash dams built with minimal materials provided water to float logs that had been placed in streambeds waiting for water. Crib, or frame, dams were bigger, more permanent structures. Logs were floated behind these dams until gates were opened and logs flowed downstream. One of these dams on Big River was built with one million board feet of lumber. A third kind of dam was called a cutaway and only used once. These were built to get enough water up to get logs floating and arranged for their trip down river. The cutaway dam left no remains after its use. It was a temporary, but vital structure.

Dams were stair-stepped up the tributaries and forks of Big River. The first dam was constructed on the Little North Fork of Big River around 1860 and the last dam was built in 1924 on the Big North Fork. The South Fork, reaching up to Orr’s Hot Springs, had 13 dams. The biggest dam launched logs on a 42-mile trip to the main stream of Big River. Because logs and water traveled about four miles per hour, trips to the mill could take nine hours. Often the timed release of water from five dams on side streams helped move everything along.

Log jams, or sacking, were a constant problem. To “unjam” a waterway the men needed more water, bull teams, steam equipment, explosives, or very hard work. Some clogge d waterways had logs stacked 30’ high before they finally broke apart—sometimes after as much as five years. To see a little log jam today, drive 12.5 miles up the Comptche-Ukiah Road and look down into the streambed. Now imagine one a thousand times bigger.

d waterways had logs stacked 30’ high before they finally broke apart—sometimes after as much as five years. To see a little log jam today, drive 12.5 miles up the Comptche-Ukiah Road and look down into the streambed. Now imagine one a thousand times bigger.

Mendocino historian Francis Jackson began research for this book decades ago with a “simple little map” he produced with the help of old timers and lumber company records. But, as many historians discover, once you have a map, you want to know when sites were built, who built them, and how long they lasted. The fact collecting goes on for years. Finally, however, the 160-page book was published in 1991. It is full of photos and stories about the people who built the dams and ran 62 logging camps, and about the equipment they used. There are also interesting facts about water in our county.

For example, if a raindrop falls on a hilltop west of Willits and breaks into three droplets, two of the droplets will enter the Pacific Ocean 97 miles apart: one droplet will enter the Eel River and hit the ocean near Ferndale; the second droplet will flow into a creek that heads to the Russian River and enter the ocean at Jenner; the third droplet will flow into Big River and join the ocean at Mendocino.

“Big River Was Dammed” is well indexed, so if there is a person or place near Mendocino you are looking for, you may find it there. The text, photos, and maps can lead you to hikes in many interesting places. The increasingly rare book is available for purchase at the Kelley House Museum.