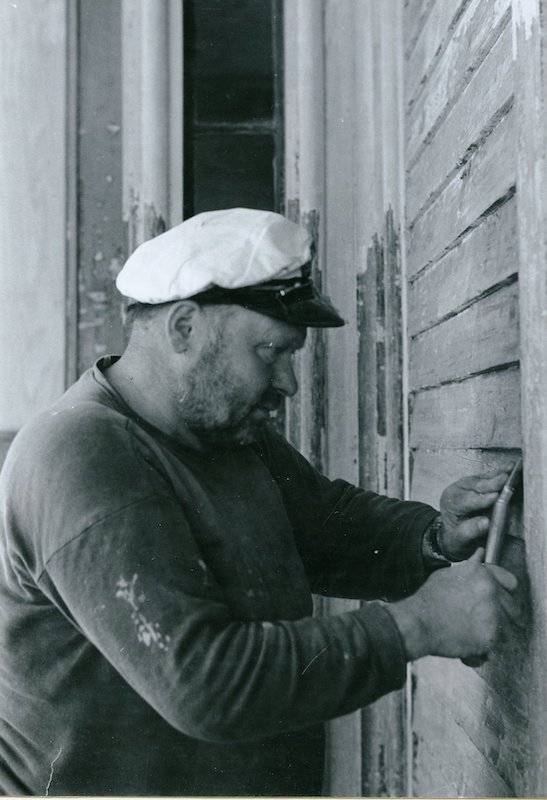

Johnny Granskog scraping paint off the Kelley House in 1975. (Photographer: Michael MacDonald)

Many of the people who had a hand in the restoration of the Kelley House 50 years ago are no longer with us. However, some were barely out of their teens when they got involved in sanding, scraping, stripping, and clipping, and they are still around. They have wonderful stories about those days, and unique perspectives on what the Kelley House meant to the community. One such young whippersnapper was Karen Latham, who arrived here in 1974, and I interviewed her recently.

After her 1972 graduation from high school in Berea, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland, Karen found her way to Humboldt County, enrolling in the College of the Redwoods in 1973. There she met and married Josh Lowell, a Mendocino lad, and with him she soon moved to Mendocino, taking up residence on the property of his mother, Laurel Moss, on the Comptche-Ukiah Road.

It was right around the time Beth Stebbins and Dorothy Bear, the founders of Mendocino Historical Research, Inc., were given the Kelley House by R.O. Peterson. Peterson, a prominent restaurateur and hotelier, had purchased the Mendocino Hotel property in order to restore and reopen it. The land happened to include the house, in which he had no interest, so he gifted it to MHRI in April of 1975.

The house had been falling apart for years and much had to be done to put it back together again: foundation work; repairs to porches, windows and siding; paint; and roof repair and shingling. And that was only the exterior. Dorothy and Beth engaged a hodgepodge of workers—seasoned professionals and rank amateurs, paid and volunteer, young and old, stoned and unstoned. Karen and Josh heard from a friend who was clearing weeds at the Kelley House that they could get part-time work there.

They joined the crew cleaning junk out of the house, ripping up old linoleum, and trying their hands at elementary carpentry. In the yard, Frances Casey was in charge of hacking back blackberry vines and noxious vegetation. The structural work was directed by Francis Jackson, a seasoned local contractor, following plans drawn up by Sam Waldman, a couple years into his architectural practice. Bob Collier was engaged to replace the redwood gutters and the gingerbread, as well as to paint the exterior of the house. He brought along Johnny Granskog, a retired mill worker, who offered to scrape the worn paint off the siding, the shutters, and the porches.

Stebbins and Bear, who founded MHRI primarily as a research organization, and who most enjoyed photographing historic homes, interviewing old timers, and writing about Mendocino’s history, did not originally dream of having the house. They knew that restoring and maintaining it would take time and resources, both of which would have to be redirected from research. However, they recognized the significance of the house to the history and landscape of Mendocino, so they began what would turn out to be a ten-year restoration effort.

Concerned about protecting the house while it was under construction, they asked Karen and Josh to be caretakers while living in the Kelley House kitchen (now the museum’s office). It was gutted and walled off from the house, a bedroom was created on its western side, and a very small bathroom installed there (now the curator’s office). Karen and Josh moved into these plush digs and lived there for about five years, exchanging their work on the house for rent.

In addition to endless interior tasks, Karen remembers installing a brickwork path from the back door of the house into the garden. She painted the flagpole that went up on the front lawn in 1979, shaved and smoothed out of a 40-foot redwood that Bill Lemos cut on his property. One winter she helped with the inventory of historic buildings undertaken by Eleanor Sverko.

Once restoration began on the house’s interior, Beth Stebbins, with her photographer’s eye, directed the work. She was very concerned that an authentic look be maintained. That was challenging in rooms with threadbare carpeting, paper peeling off the walls, and layers of paint slapped on over the years by renters. Old photos of Kelley family members taken inside the house helped, though they were sepia, and advice came from the California Office of Historic Preservation, part of California State Parks, which was reviving the Ford House across the street. On the wall in Beth’s office on the first floor, in what is now the Lemos Library, she hung a framed maxim: “Better to preserve than repair, Better to repair than restore, Better to restore than rebuild.”

Eventually, the house was made structurally sound, detailed appropriately, and decorated suitably. However, it was more than a handsome landmark or a frilly house museum, in Karen’s opinion. It provided a valuable gathering place, but, more than that, it was a community builder. Individuals and groups as various as the high school senior class, businesses, and the Daughters of the American Revolution donated funds. Old timers and newcomers worked together on it. “We created something special,” she said; “It was bigger than itself.”

The Kelley House Museum is open from 11AM to 3PM Thursday through Monday. If you have a question for the curator, reach out to curator@kelleyhousemuseum.org to make an appointment. Walking tours of the historic district depart from the Kelley House regularly.