In recent weeks, the Kelley House Calendar has focused on log rafts and the vessels pulling them. Log rafts were exactly what the term suggests, logs tied up with chains that were towed to a sawmill in a sunny location where sunshine could dry out fresh cut boards. Practiced from 1906 to 1942, rafts became the cheapest way to move a lot of logs 1,000 miles to the south of the Mendocino coast.

Fort Bragg Lumber Company tried the idea in 1892 but didn’t have a lot of luck and lost more than one raft under tow. Rafts would break up in rough waters, cause marine transportation disruptions, and litter the shore with logs. Big timber mill operators like Hammond in Humboldt and Benson on the Columbia River were the ones who perfected the design and shipping of log rafts, but even they experienced occasional disasters.

In 1938, the logging industry was not experiencing the brightest of times. Deep into the Great Depression the Mendocino sawmill, then owned by Union Lumber Company, had been shuttered but not yet dis-assembled and sold as salvage. It was a log raft accident that gave the mill one last moment of glory.

In mid-August of that year, a huge Benson log raft broke in half in rough seas at Needle Rock on the Lost Coast of northern Mendocino County. To try and salvage what they could, the raft’s tug operator needed a deep-water harbor that was easy to enter and with maneuvering room. The tug operator did not want to see a valuable log load lost, or have it broken up on offshore rocks. So, the tug in charge pulled half the load toward Mendocino while a second tug sent from San Francisco came to get a line on the other half of the raft.

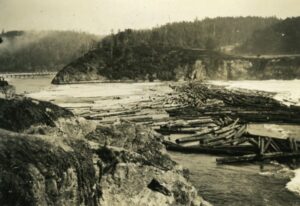

The tug pulled the broken half-raft into the mouth of Big River and an eight-inch-thick manila rope connected it to the shore. The second half of the load arrived a day later, as two miles per hour was as fast as the tug could pull the damaged raft. Safely moored, the Benson Lumber Company began negotiations with the local mill to see if the logs could be turned to lumber in the closed Mendocino sawmill.

The broken raft represented a minimum of two months’ work for the mill, and the sawmill workers would be happy to return to work. The raft had five million board feet of lumber in it, being nearly 1,000 feet long and 55 feet wide. While it wallowed in Mendocino Bay, the headlands were lined with locals and tourists looking down at the disarray. The raft, composed of fir, red cedar, and spruce logs, and had been valued at $100,000 when (and if) it arrived in San Diego. It was the 110th log raft Benson had assembled and shipped.

A boom barrier was assembled around the floating mass of logs and work began to break up the load and remove the raft’s chains, valued themselves at $10,000. The logs were pulled by motor launch over the river bar and up the river to the mill. Rough seas in September further broke everything up and the beach was reported by old-timers to be six feet deep in logs, with those that had escaped the boom scattered up and down the coast.

An estimated 1,200 logs went to the mill and were turned into 150,000 board feet of lumber. By November, the steamer “Noyo” was hauling deck loads of that lumber to San Francisco. The job was done, the Mendocino sawmill was closed, and then the mill site was scrapped.

What led to the ending of log rafts shipments will be explored in a future Kelley House Calendar.