Down in the archives of the Kelley House, I was working on a research project tracing a local family’s name through graveyard records when I found something that answered questions I’d long had about the images on gravestones. The Victorians were engravers of images, along with words, on headstones and I found animals, body parts, geometric shapes, plants and objects all had symbolism discussed in the materials I read.

Doves were a symbol for Christianity, the Holy Spirit and purity. Eagles represented courage, owls stood for wisdom, and dogs denoted loyalty. Dragons bespoke triumph over sins and fish equaled faith. Lions represented the power of God and lambs on a child’s grave showed innocence, meekness and humility. A serpent swallowing its tail stood for eternity.

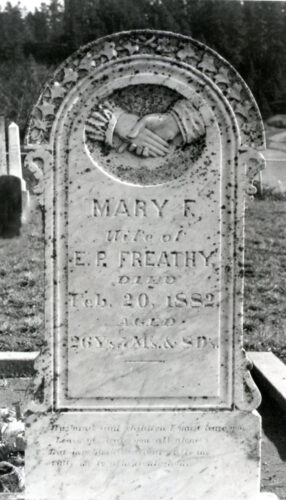

Body parts on headstones included outstretched arms as a plea for mercy. Eyes represented the all-knowing and ever present God, and hands were a symbol of leaving. Hands clasped denoted a married couple, but if the hand held a chain with a broken link it denoted the death of a family member. A heart on a headstone stood for love or God, courage and intelligence and if there were flames engraved around the heart the deceased had great religious fervor.

Geometric circles denoted eternity. Two circles, one above the other, were earth and sky. Three interconnected circles stood for the Holy Trinity. A pentagram or five-sided star represented a spirit rising to heaven. A headstone with a triangle on top prevented the devil from reclining on the grave.

All sorts of objects were carved on gravestones. Anchors were symbols of hope and indicated seafarer’s graves. Arches stood for victory, arrows for mortality. Books appear on scholar’s gravestones and a broken column indicated a life cut short. Doors or gates on stone were passages into the after-life and keys denoted spiritual knowledge.

Buttercups on a headstone represented cheerfulness, daffodils stood for the death of youth and daisies for childhood innocence. Ivy represented friendship and honeysuckle bonds of love. Wheat denoted the divine harvest and resurrection and broken rosebuds pointed to a life cut short or a young person’s grave.

Looking at graveyard records, I was delighted by the wonderful first names of those who reside in our cemeteries. Listed here are names we seldom see or hear today and reflect the diverse ethnic makeup of the coast. There was Hansid, Adah, Jens, Flavia, Delmer, Ruel, Karoleena, Ezio, and Signe. Who were Olen, Yerda, Ansel, Gemme, Eri, Veryle, Sophrony, Hellan, Pehr, Toney, Aita, Zebedee, Phena, Sime, Pehr, Hagar, Telithe and Toivo?

Other great names were Softina, Perley, Robley, Lipa, Roarick, Previlla, Varks, Jabes, Mather, Callon, and Abial. Someone’s ancestors were Dreeme, Reino, Kothee, Pazcual, Ansano, Marzelette, Versageo, Juki and Ocinzo.

The above column appeared in our Kelley House Calendar published on January 20, 2011. Cemetery research continues today at the Museum as we bring our extensive records up to date and collate them into modern digital formats. If you find cemeteries as fascinating as we do and would like to assist with this effort, give us a call at 707/937-5791, or write to us at curator@kelleyhousemuseum.org.