Christmas is going to be different this year. 2020 has been a difficult year of anxiety, separation, and loss and with the holidays, we should be looking forward to getting together with friends and loved ones to celebrate the season.

Instead of gathering, we will be isolating as we are reminded of the pandemic that is sweeping our nation. We are fortunate these days to have technology to make this separation easier. We can call, text, Facetime, Skype and Zoom, making the presence of others feel a little bit closer. This was not the case in an earlier time when families and friends in Mendocino were experiencing similar emotions about not being able to be together while worrying about the loved ones that they could not see. It was the winter of 1861.

William and Eliza Kelley had just moved into their newly built house on Main Street with their two-year-old daughter, Daisy. It should have been a joyous time; the holidays were coming soon. But in December 1861, the North and South had been embroiled in a civil war for many months. Early hopes on both sides for a speedy conclusion had been put to rest and the warring sides prepared for a longer conflict. Mendocino was far from the front lines, but many of her sons were not. The hopes for a joyous Christmas celebrated with beloved family members were replaced with the realities of separation, longing, isolation and the fears of war.

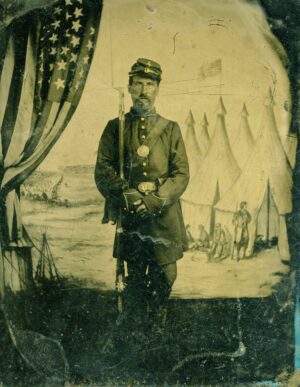

The towns of Mendocino and Little River were founded by many people from New England. As many as 37 families from Maine settled in Mendocino. Another 23 families from Maine settled in Little River. During the Civil War, Maine was a source of military manpower, supplies, ships, arms and political support for the Union Army. About 80,000 men from Maine served in the U.S. military as soldiers and sailors. Hundreds of civilians served as nurses, doctors and relief workers at home or on the battlefield.

Although the Kelleys came from Prince Edward Island in Canada, almost all of their friends and neighbors were from the East Coast and almost all had family fighting in the war. For many, the holiday was a reminder of the profound melancholy that had settled over the entire nation. On the Confederate home front, Allie Brock Putnam of Richmond, Virginia, wrote, “Never before had so sad a Christmas dawned upon us. We had neither the heart nor inclination to make the week merry with joyousness when such a sad calamity hovered over us.”

The war intensified Christmas’ appeal. Its sentimental celebration of family matched the yearnings of soldiers and those left behind. Its message of peace and goodwill spoke to the most immediate prayers of all Americans. Thomas Nast, illustrator for the magazine Harper’s Weekly and father of the American cartoon, created prints illustrating the longing born of separation that became more amplified during the Christmas celebrations.

One such illustration titled, “Christmas Eve” depicts a wife, on the left, in earnest prayer on Christmas Eve, praying for her husband, while her children sleep quietly in the background. On the right is her husband, a soldier far from home and isolated, pining over pictures of his loved ones. Surrounding the main images are illustrations that express the complexity and contradictions of celebrating the peace and joy of Christmas while experiencing the pain and separation of war. Nast was a fierce supporter for the Union cause who skillfully used allegory and melodrama in his art to support the cause he believed was just. By Christmas 1862, Thomas Nast had introduced a modern version Santa Claus united with the Union Army.

Thus began the creation of an “American Christmas,” much as we know it today, that was a response to the social and personal needs of the time. The invention of new customs and meanings helped the nation to make sense of the confusion of the era and to secure, if only for a short while each year, a soothing feeling of unity. The swirl of change caused many to long for an earlier time in which they imagined that old and good values held sway in cohesive and peaceful communities. It also made them reconsider the notion of “community” on a national scale but modeled on the ideal of a family gathered at the hearth. It revolved around home, relatives and children.

Above all seasons, Christmas accentuated the absence of those who went to war, the families left behind and the soldiers themselves. Civil War soldiers in camp and their families at home drew comfort from the same sorts of traditions that characterize Christmas today. John Haley, of the 17th Maine, wrote in his dairy on Christmas Eve that, “It is rumored that there are sundry boxes and mysterious parcels over at Stoneman’s Station directed at us. We retire to sleep with feelings akin to those children expecting Santa Claus.”

Artist Winslow Homer’s illustration “Christmas Boxes in Camp – 1861” depicts the merriment soldiers experienced when they received boxes from home on Christmas. Homer created this image while camping with the Union army in Virginia as a “special artist” covering the front lines for Harper’s Weekly. In it the soldiers have tossed aside their books in favor of newly delivered socks, mittens and home-cooked treats. The somewhat sentimental engraving illustrates the spontaneous joy that Christmas presents inspired among the soldiers. The care package, in a box labeled “Adams,” contains all the things needed by tired and ragged soldiers. The box is full of good things to eat. Several soldiers appear to be enjoying bread and pastry items. Perhaps even more important than the food, the box appears to be full of socks and footwear. Ultimately, the illustration was meant to lift the spirits of the dedicated women who sent such packages to the front.

Christmas during the Civil War served both as an escape and a reminder of the awful conflict tearing the country in two. Soldiers looked forward to a day of rest and relative relaxation and, at home, families did their best to celebrate the holiday while wondering when the vacant chair would again be filled. The war lasted for four bloody years with almost 700,000 dead. By the last Christmas of the war, the Christmas of 1861 did not seem so hard after all. The war’s end brought better hopes for holidays to come. Five years later, in 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant made Christmas an official holiday in hopes of bringing reconciliation to a fractured nation and uniting the North and South.