by Sarah Nathe, Kelley House Museum Board secretary

We left off last week puzzling over the incongruities inherent in the Improved Order of Red Men, a fraternal organization for white people that patterns its costumes, rituals and terminology after early Native Americans. Photos in the Kelley House archives show Red Men parading around town in Indian getups, tomahawks, tom toms and American flags in hand. Grown men?

This phenomenon has been so prevalent in the USA that you can write a book about it — many, in fact. In his 1924 Studies in Classic American Literature, D.H. Lawrence observed: “There has been all the time in the white American soul, a dual feeling about the Indian. The need to extirpate him, and the contradictory desire to glorify him. Americans have continually wanted to have their cake and eat it too.”

Lawrence understood that the new Americans were products of European civilization, with its rational mindset and prescribed social order. By those lights Indians were uncivilized savages. At the same time, however, Indians represented instinct and freedom — “the untamed spirit of the continent”– and white Americans aspired to be liberated inhabitants of the New World.

Philip Deloria, a Dakota historian, tackled the great American ambivalence more recently in Playing Indian (Yale University Press, 1999). Alluding to Lawrence’s ideas, he notes that white Americans could not be aboriginal, but they could put on an aboriginal costume and enjoy the feeling it gave them [a certain “American-ness”] until the masquerade was over:

“Playing Indian is a persistent tradition in American culture, stretching from the national big bang into an ever-expanding present and future. However, this creation of ‘nationalness’ has from the Constitutional Convention forward been the domain of white males. They have built their identities on contrasts between their own citizenship and that denied to women, African Americans, and even Indians.”

“Playing Indian is a persistent tradition in American culture, stretching from the national big bang into an ever-expanding present and future. However, this creation of ‘nationalness’ has from the Constitutional Convention forward been the domain of white males. They have built their identities on contrasts between their own citizenship and that denied to women, African Americans, and even Indians.”

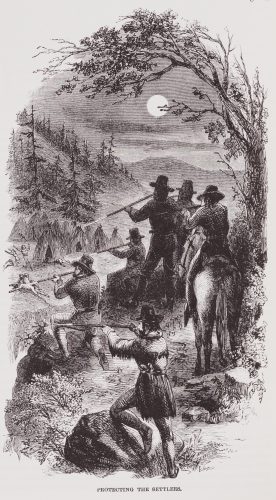

The Fort Bragg tribe of Red Men was established in 1888, one year after the Round Valley War, when white settlers tried to take over reservation areas deeded to the Yuki, and only 28 years after the end of the Mendocino County War, the round-up and slaughter that had relegated the Yuki to the Round Valley Reservation in the first place. In the eight years between 1852 and 1860, white intruders had reduced the Native American population in Mendocino county by nearly 80% (Baumgardner, Killing for Land in Early California, Algora Publishing, 2006).

Did the local Red Men see the cruel irony — not to mention hypocrisy — in their play-acting? And the current IORM members in 15 states (including California) — what do they think they’re doing? Check out the organization’s web page if you really want to know: www.redmen.org.

Photo captions: The drawing at top accompanied an 1861 Harper’s New Monthly magazine article about the mass murder of Yuki people at Round Valley. The photo immediately above shows the Red Men tribe in the 1905 July 4th parade in Mendocino.