by Sarah Nathe, Kelley House Museum Board secretary

by Sarah Nathe, Kelley House Museum Board secretary

Two weeks ago at the opening of the new Kelley House exhibit, “Medicine on the Mendocino Coast: Say Ahh…”, I was looking at pioneer druggist C.O. Packard’s prescription ledger from 1882 and wondering about some of the potions and pills he dispensed. I noticed a “Morph. Sulph.” prescription for a Mrs. Johnson, a “Cocaine Wine” prescription for a Mr. Hardy, and a “Codeine” prescription for a Mr. Gibbs for Rosie. Rosie must have had a bad cough.

Charles Oscar Packard became Mendocino’s druggist in 1877 when he and his brother purchased R. H. Witherell’s drug and jewelry store on Main Street. Packard had been a logger in Comptche and along Big River for eight years previously, but “Dr. McCornack persuaded him to learn the drug business and helped him fill prescriptions,” according to his daughter, Hazel Packard Dennison (“Kelley House Calendar,” Mendocino Beacon, January 5, 1978). So that’s all it took to turn a lumberjack into a druggist who could compound medications (opiates at that) and sell them: a little help from Dr. McCornack?

Well, yes. According to a 2016 article in The Guardian (“The strange history of opiates in America: from morphine for kids to heroin for soldiers,” by James Nevius, March 15), in the 19th century there was little distinction in the United States between apothecaries and druggists; both could legally formulate and dispense every drug from their own patented elixirs to remedies prescribed by doctors, some of which were narcotics. The efficacy of most patent medicines was questionable, though they were heavily advertised and sold like hotcakes. However, the ones that contained morphine, codeine, cocaine, heroin (!) and alcohol–or a combination–really did the trick!

If we have an opioid crisis now, we had its precursor in the second half of the 19th century. The Civil War, with its attendant carnage, had introduced the United States to morphine, isolated from opium in 1827, and to the syringe, invented in 1853. The seriously wounded soldiers were treated with morphine, and thousands of battle-scarred veterans on both sides returned home as addicts. With no government regulations and entrepreneurs peddling morphine in many attractive forms, the “soldier’s disease” spread to other sectors of the populace.

To help lift people out of their morphine-induced fog, medical authorities began touting the benefits of other newly discovered opiates (in one of American history’s bigger blunders into unintended consequences). Cocaine-infused wines and other beverages, which had become commercially available in Europe in the 1860s, caught on in the states; sales soared almost the minute Coca-Cola was offered at an Atlanta pharmacy in 1886.

Diacetylmorphine, refined in Germany in 1876, was marketed by Bayer as “Heroin” in the 1890s; advertised in the United States as an effective cure for aches, pains, nauseas, bronchial problems, sleep disorders, and “over-reliance on morphine,” it quickly eclipsed aspirin as the company’s best-selling product.

Not until 1906, when the federal government passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, were patent medications required to note “dangerous” or “addictive” drugs on their labels. No restrictions were placed on the sale of opiates until the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, but that law didn’t ban their import, distribution and sale; it taxed them and required buyers to have a prescription from a licensed physician. After that, the use of opiates declined–for a few decades.

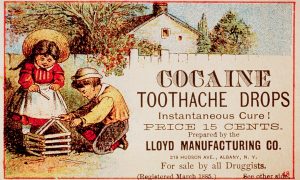

Photo caption: In the 1880s, cocaine was thought to be an effective local anesthesia that offered the possibility of pain-free dentistry, so Charles Lloyd did not hesitate to list it as an ingredient in his “cure.”